A global study led by a researcher at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and published in the journal Scientific Reports finds that economic inequality on a social level cannot be explained by bad choices among the poor nor by good decisions among the rich. Poor decisions were the same across all income groups, including for people who have overcome poverty.

Study here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-36339-2

The title of this article is /r/Politics levels of editorialising. I half expected to read, “our conclusion is that conservatives are clearly dumber.”

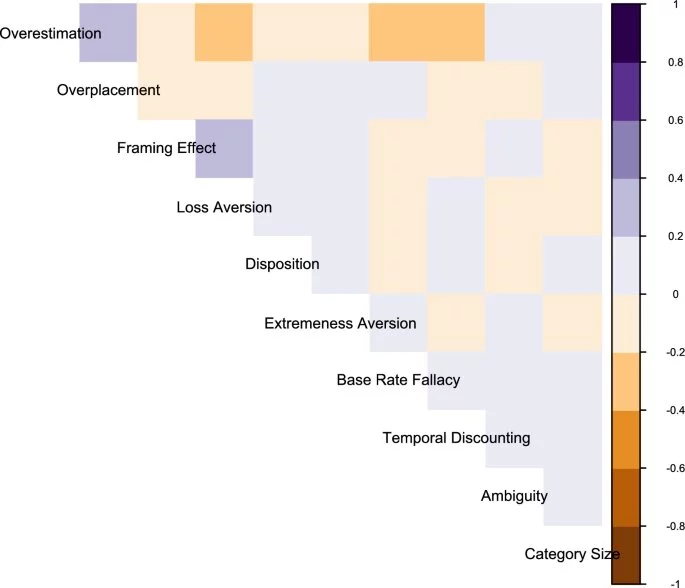

The study used some simple tests to measure certain cognitive biases respondents might possess. Unsurprisingly, poor people are human, and subject to the same amount of bias as everyone else. This doesn’t test the title of this submission - choices - at all. In fact the authors go to great lengths to explain this:

Sorry but how does the title not just slightly rephrase the paragraph you quoted? Seems like Kai Ruggeri is saying that their study concluded that poor people making poor choices is not a sole explanation for economic inequality.

It’s completely different. Everyone has cognitive biases, so measuring whether the poor have more cognitive biases or less doesn’t mean anything except that they have the same cognitive biases as anyone else.

That doesn’t speak to the quality of their decisions. The idea that you can’t make your life better or worse by the decisions that you make is self-evidently wrong. The only way that you could think that you can’t make your life better or worse by making better or worse decisions it’s if you’ve never made a decision that had any consequence.

You can share the same cognitive biases as everyone else and still make better or worse decisions. As a general rule, people who practice self control and defer gratification are going to do better than people who do not practice self-control and do not defer gratification. Of course it’s not always true, sometimes you roll a one. But in general, we know that certain types of decisions are going to have better outcomes and other types of decisions are going to have worse outcomes.

Sometimes the exact same cognitive biases can justify polar opposite ends. For example, optimism bias could play out in such a way that somebody makes incredibly poor decisions and justifies it thinking that everything will be okay anyway. On the other hand, the same optimism bias could play out in such a way that somebody makes better decisions and justifies it thinking that if they do everything they need to then everything’s going to be okay. Both ways could turn out to be wrong.

Yet another bias that we have is neglect of probability. Somebody who makes good decisions or somebody who makes bad decisions could use the exact same faulty logic that doing what they were going to do has a chance of helping them become a billionaire. In both cases, the chances of becoming a billionaire are infinitesimal, but the cognitive bias can justify both positions. Hang on to that piece of information for a minute it becomes important later.

One of the most studied cognitive biases is anchoring bias. In this cognitive bias, a recent piece of information ends up coloring the decisions that are made. Depending on what the last piece of news that you heard was, the cognitive biases that you have may end up supporting the idea of doing the right things, or they may end up supporting the ideas of doing the wrong things, and it’s almost random what the last thing that you heard was.

I could go on listing different cognitive biases and how they can potentially affect our judgments, and all of them would be true. But what would not be true is that the decision that you make doesn’t matter. The decisions that you make matter more than anything. That’s why if you want to have a good life, and you had a choice between being a couple standard deviations above average and intelligence or being a couple standard deviations above average in wealth, you would choose intelligence because it would help you make better decisions that would lead to better outcomes than just having a bunch of wealth available for you to blow.

That was a lot of words to not actually address what I said.

It directly addresses what you said. The study investigates cognitive biases, and the title talks about “poor decisions”. The two are completely different things, as I explained in depth.

I’m wondering if there is any research which directly addresses the correlation level between cognitive biases and poor decisionmaking.

It feels like commonsense that there should be a causal relationship in there, logically speaking, but “common sense” isn’t science.

The association between the cognitive biases of the tested psycho-metrics and poor decision making with regards to socio-economic outcomes aren’t tested or even cited in the study. To draw a causal conclusion you would need to investigate and confirm that. Put simply, A does not imply B.

Does this mean r/Politics is in stage 4?